The European used car (UC) market is seeing unparalleled attention and investment. While OEMs have long understood the links between new and used markets, they typically exercised only indirect control over second and third transactions. New, well-funded channels have emerged, as OEMs struggle to simultaneously manage the powertrain transition and investments in software-enabled vehicles. OEMs’ pursuit of downstream value is creating a clash with the disruptors: UC supermarkets, vertically integrated competitors, and digital platforms. This Viewpoint explores this clash, how OEMs are responding, and implications for the UC ecosystem.

WHAT’S DRIVING THE CLASH?

The post-pandemic landscape

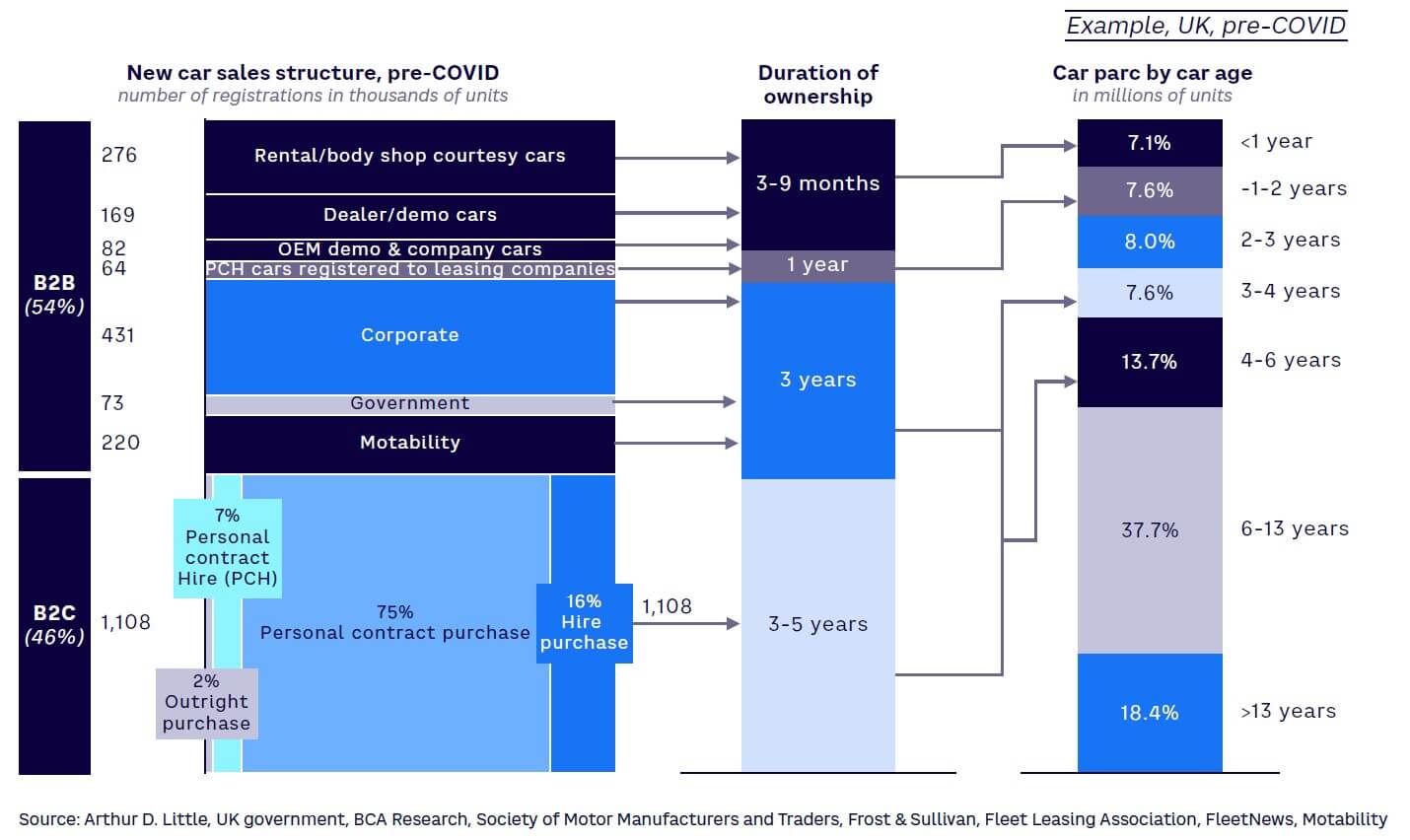

The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic heavily affected both new and UC markets. In Europe, the new car market shrank by approximately 25%. This decline reduced the supply of vehicles to the UC market, which typically happens any time from three months to five years after a new vehicle’s initial sale, depending on the channel.

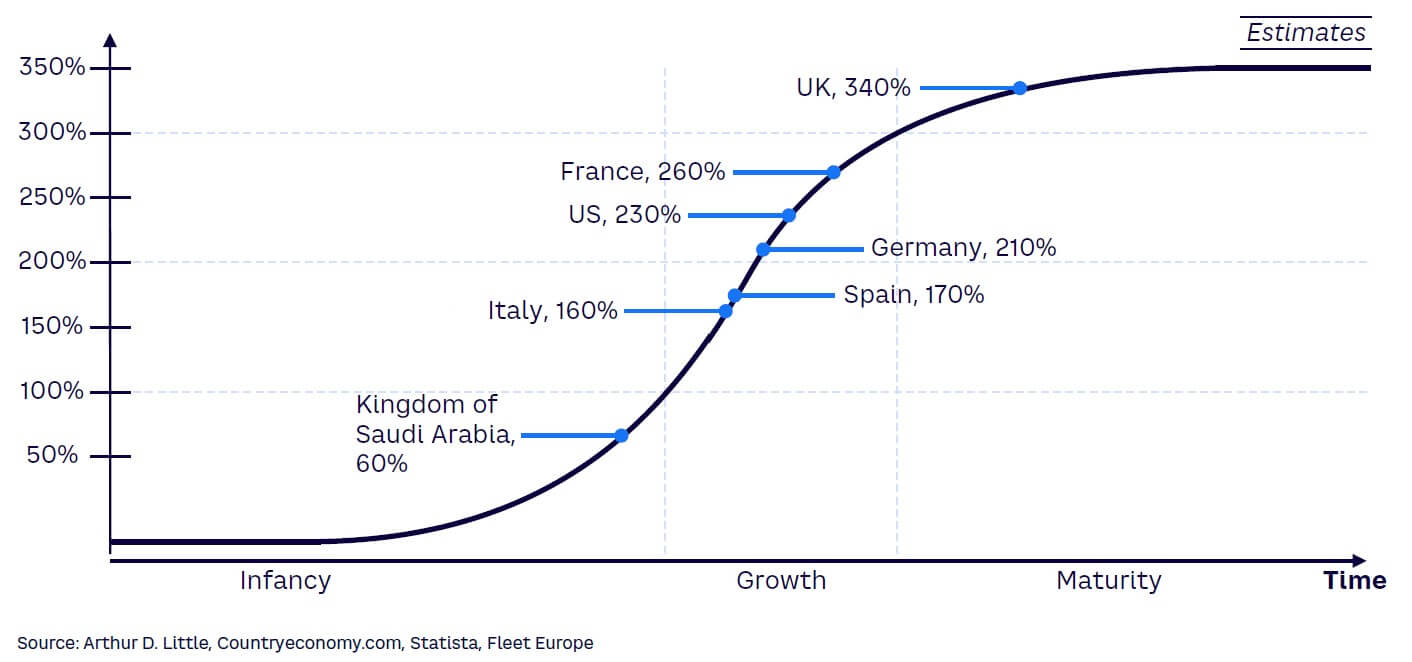

The ratio of new car transactions to UC transactions varies by country. Pre-pandemic, it ranged from fewer than one UC transaction for every new one in Saudi Arabia to three to four UC transactions per new car transaction in the UK (see Figure 1). In Europe, the long-term average is between two-and-a-half and three, with vehicles typically changing hands at two to five years, five to 10 years, and 10 years of age or older.

In 2022, the UC market grew to EU €570 billion. The ratio of used to new car transactions rose to unprecedented levels across Europe. The global shortage of computer chips dramatically cut the supply of new vehicles, resulting in order backlogs of anywhere from three to six months (as with Asian OEMs) to over a year. Frustrated customers, unable to buy new cars, were forced to turn to “new-used” vehicles, which have also been in increasingly short supply (see Figure 2).

Temporary fluctuations aside, the UC market has been growing at 0.5%-1% per annum, driven by lengthening vehicle life spans and shorter average new car holding periods. The pandemic lockdown led to a 25%-30% decrease in the new car market between 2019 and 2021, which reverberated into UC sales volumes with a lag of one to three years, resulting in an 11% reduction in 2022. Nevertheless, Arthur D. Little (ADL) expects this secular volume growth to return in 2023–2024 as pandemic-related disruptions continue to dissipate.

The rise of the UC market

Though long-term trends in the UC market will continue to hold, two shifts in the new vehicle market will drive further UC market growth:

-

Increased financial services penetration, specifically operational leasing, as EVs (which have higher initial prices and lower running costs than their ICE cousins) will represent two-thirds of new vehicle sales by 2030, which will shorten the average vehicle first-life.

-

The growth of “fleet as a service” (FaaS) and subscription models will add a new segment with a relatively short holding period, whether the first owner is an OEM business unit or a third party.

Other influences

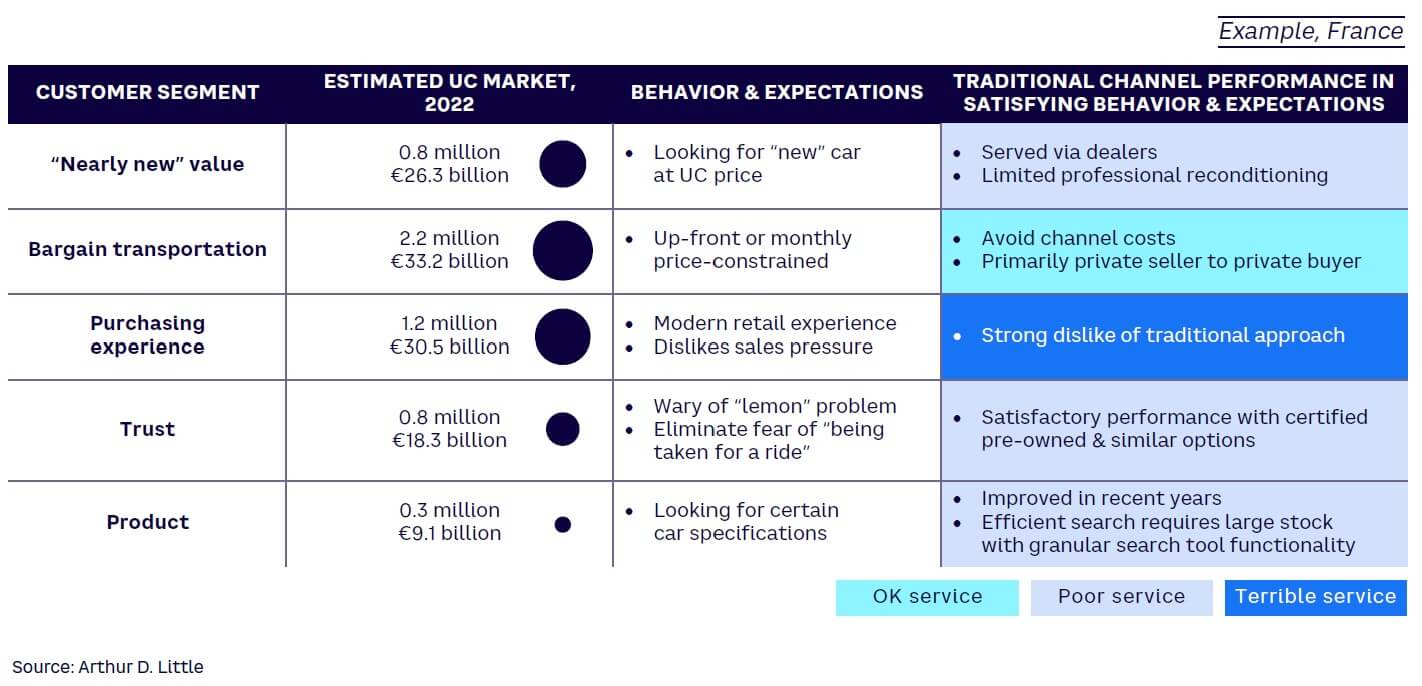

Traditionally, retail channels have consisted of franchised dealers, independent UC dealers, and direct consumer-to-consumer sales. Although this structure successfully channelled millions of cars from one owner to another, it left much to be desired for many UC buyer segments (see Figure 3).

For example, the current generation of consumers seeks a more modern car-buying experiences. A number of new entrants to the UC market have taken notice of the opportunity these consumers present and have created new channels ranging from multi-brand car supermarkets to purely digital sales models.

Many of the above challenges are inherent to the UC market, where the seller knows more about the vehicle than the buyer, and the buyer seeks reassurance and information about their potential purchase. Certified pre-owned programs and other forms of warranty are responses to the concerns presented by buyers who worry about purchasing a “lemon.”

OEMs FORGE AHEAD

UC sales

As the used vehicle segment evolves, broader transformations in the new car distribution model are causing OEMs to take a larger role in UC transactions. Two factors drive this evolution:

-

Powertrain shift. The transition to electric powertrains for passenger cars is definitively underway, with roughly two-thirds of European new registrations expected to be xEVs (hybrid or fully electric) by 2030.

-

Changing dynamics between OEMs and their distribution points of sale, which are transforming the traditional franchised dealer model.

The coexistence of distribution models for ICE vehicles and EVs is creating profitability challenges for OEMs. The higher up-front price of EVs puts pressure on new vehicle margins, which — given the low profitability of new car dealers — fall heavily on OEMs.

Moreover, these difficulties are happening at the same time that OEMs are investing heavily in organizations and people to design and build software-enabled vehicles. The impact of the chip crisis, which has increased transaction pricing across the board, has partially masked these profitability problems.

These dual pressures are pushing OEMs to seek profitability “downstream,” by setting and announcing targets to increase “service” revenues from the current 5% of turnover to 30% by the 2030s. The second transaction, when a car is sold by the original owner or their representative, is critical in this regard, as it:

-

Provides a source of revenue and margin (dealer gross margins on used vehicles average around 7%).

-

Offers an entry point for future vehicle owners, as customers for downstream services.

Rethinking new car distribution

Twenty years ago, car dealers performed the “heavy lifting” of car sales. They would convert perhaps 20% of showroom visitors to customers, guiding them “down the funnel” from product marketing and test drives to negotiating and closing the sale. Dealers had a strong incentive to collect the retail price for a vehicle they purchased wholesale from the OEM, with high stakes in terms of gross margin.

In a related parallel development, OEMs are rethinking their new vehicle distribution channels as the traditional franchise model becomes inconsistent with their changing roles and responsibilities:

-

Car dealers are now “order takers” for new cars. Around 90% of customers used an OEM online tool in advance to choose their vehicle. An agency fee is a more appropriate incentive system for executing a transaction (while creating new balance sheet and month- and quarter-end management hurdles for OEMs).

-

OEMs increasingly wish to sell through their own digital channels, which requires coordination with physical channels. Franchised dealers, with their ability to set prices, create potential channel conflict. An “agency,” where the OEM sets the price, would resolve this challenge.

- In a multichannel world, incentives need to be set and shared with multiple parties. Only the OEMs can play this role.

Therefore, we see a proliferation of cancelled dealer contracts and agency pilot programs, with some of these initiatives aimed at EVs because these vehicles were often not covered by the legacy franchise agreement.

IMPLICATIONS FOR OEMs & DISRUPTORS

The changes to both the new and UC industries will be more far-reaching than a transformation in the financial relationship. It is a short step from “agency” in new vehicles to a change in the relationship with dealers for used vehicles. While the dealer has traditionally held the right to remarket “off-lease” new vehicles, we expect OEMs to play an increasing role.

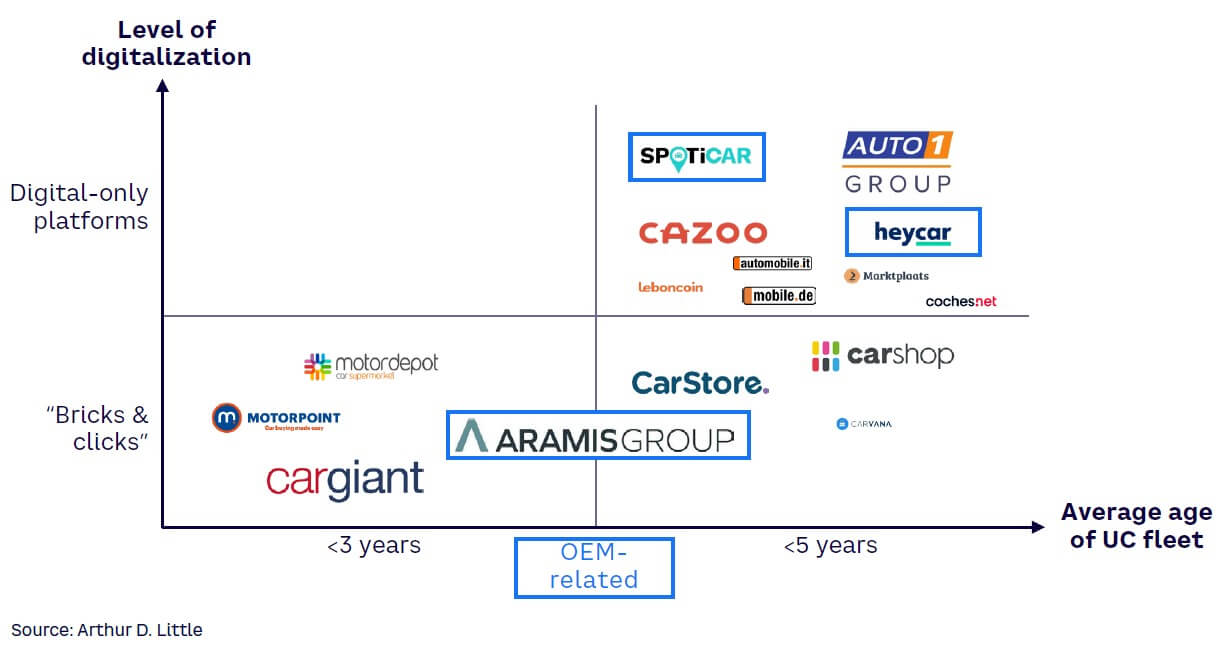

OEM used vehicle channels (e.g., Aramisauto, Spoticar, Heycar) are facing off against the new disruptors, whose models can be tailored by the degree of digitization and linked to the customer segments’ comfort or discomfort with a purely digital experience in a market that is notorious for information asymmetry and nefarious behavior. These models can also help prospective buyers search by characteristic, such as the average age of a vehicle (see Figure 4).

The emerging battle

The disruptors are well funded and have established and shared significant targets. For example, AUTO1, Carvana, and Cazoo (prior to its current problems, which were created by overexpansion) have announced plans to cumulatively sell 250,000 used vehicles in France by 2030. This would represent approximately 4% of the used vehicle market (versus 1% today) and 12%-15% of transactions for vehicles five years old and under.

The key competitive weapon of OEMs remains their privileged access to a ready supply of high-quality, young, used vehicles. As captive finance penetration increases for EV transactions, OEMs will tighten their control over these vehicles.

The disruptors will be left to source their vehicles from independent leasing companies or obtain them directly from new vehicle owners and auctions/imports. While ADL forecasts considerable growth for these digital disruptors as a group, we do not expect them to exceed 5% share by 2030, provided OEMs can execute their customer-facing value proposition.

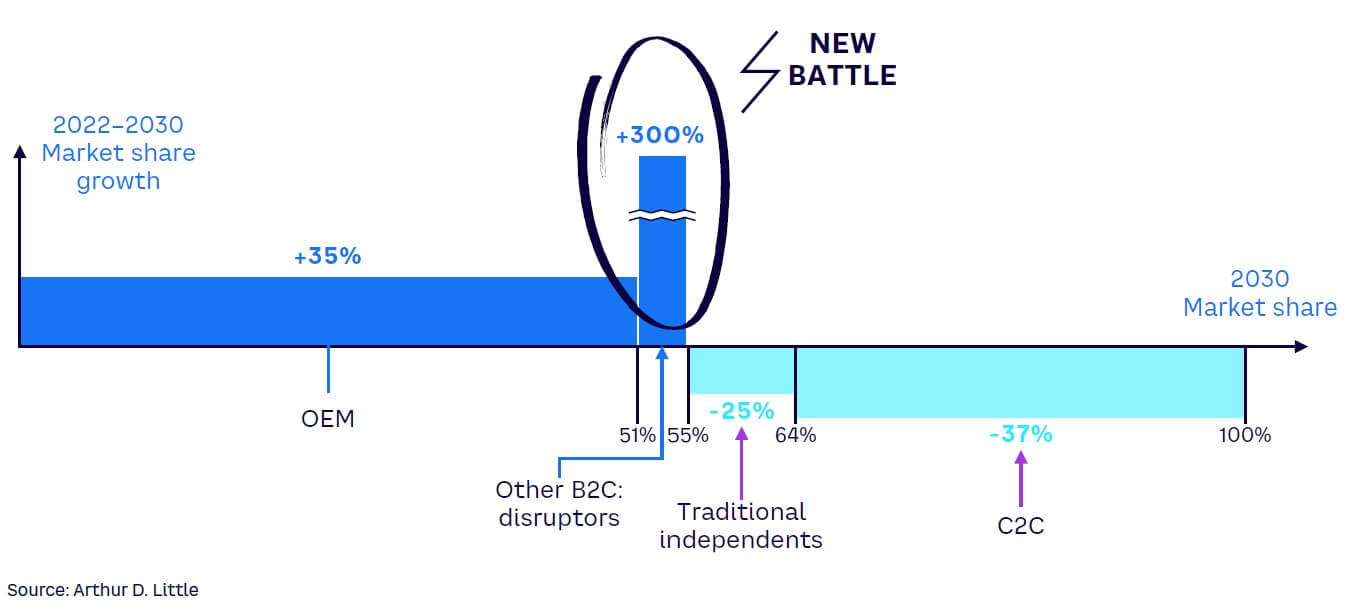

As OEMs and the disruptors battle it out, we expect private customer-to-customer (C2C) transactions to decline (see Figure 5). The local small traditional independents will be the big losers, forced to increasingly focus on rural, less digitally savvy buyers of aging (six years and older) vehicles.

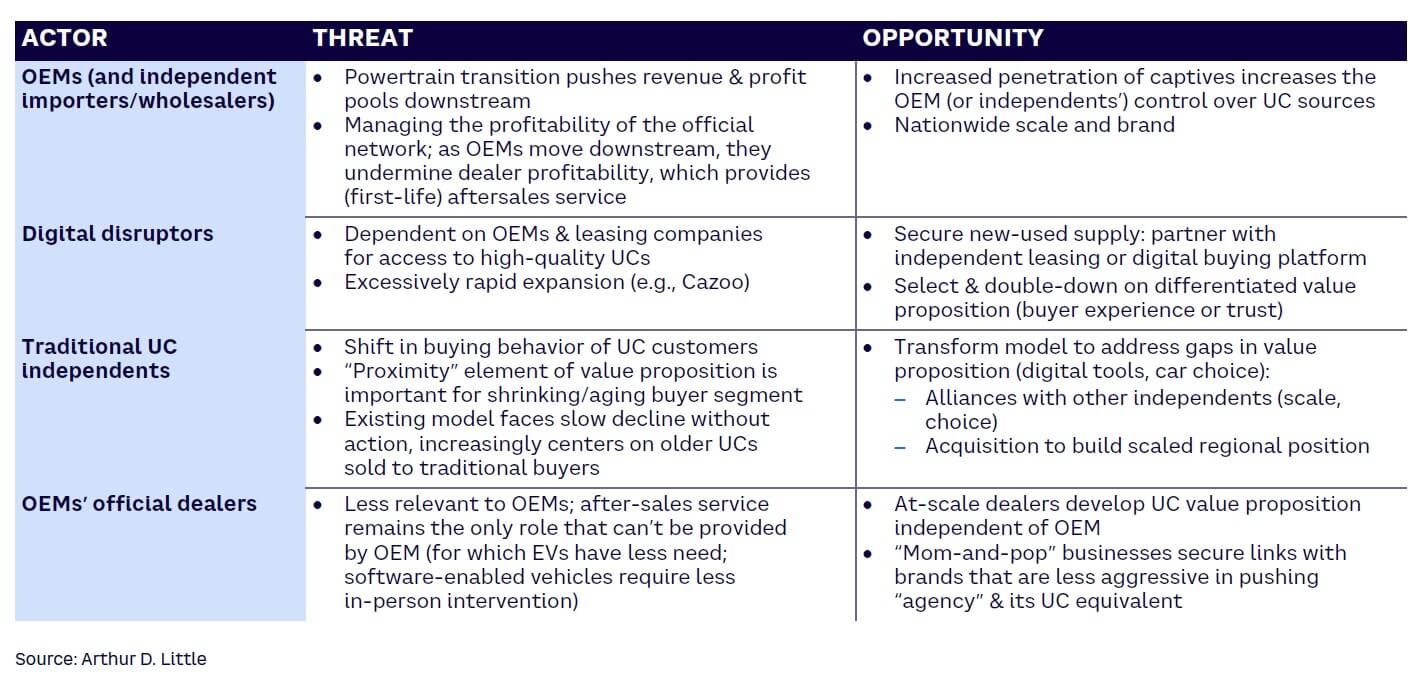

Table 1 summarizes the significant, high stakes transformation we expect to see in this €570 billion market, with OEMs structurally well-positioned to capture downstream revenue pools.

Conclusion

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF THE EUROPEAN UC MARKET

The European UC market enjoys a ratio of two to four UC transactions for every new car transaction, but uneven customer experiences made it ripe for disruption. Both vehicle OEMs and digital disruptors are laying claim to this space. The primary competitive weapon of OEMs is their control of high-quality, young, used vehicles, strengthened by increased captive finance penetration of new EV sales. We expect:

-

Considerable growth for digital disruptors, which may be constrained if OEMs achieve their customer-facing value proposition.

-

Higher OEM shares from increased control over both vehicle and customer lifecycles.

-

A substantial decline in share of the C2C segment.

-

Pressure on traditional independents that will resort to older vehicles for less digitally savvy customers.